Integers and real numbers can be represented on a number line. The point on this line associated with each number is called the graph of the number. Notice that number lines are spaced equally, or proportionately (see Figure 1). Figure 1. Number lines.

Graphing inequalities When graphing inequalities involving only integers, dots are used. Example 1 Graph the set of x such that 1 ≤ x ≤ 4 and x is an integer (see Figure 2). { x:1 ≤ x ≤ 4, x is an integer} Figure 2. A graph of {x:1 ≤ x ≤ 4, x is an integer}.

When graphing inequalities involving real numbers, lines, rays, and dots are used. A dot is used if the number is included. A hollow dot is used if the number is not included. Example 2 Graph as indicated (see Figure 3).

This ray is often called an open ray or a half line. The hollow dot distinguishes an open ray from a ray. Figure 3. A graph of { x: x ≥ 1}.

Figure 4. A graph of { x: x > 1}

Figure 5. A graph of { x: x < 4}

Intervals An interval consists of all the numbers that lie within two certain boundaries. If the two boundaries, or fixed numbers, are included, then the interval is called a closed interval. If the fixed numbers are not included, then the interval is called an open interval. Example 3 Graph.

Figure 6. A graph showing closed interval { x: –1 ≤ x ≤ 2}.

Figure 7. A graph showing open interval { x: –2 < x < 2}.

If the interval includes only one of the boundaries, then it is called a half‐open interval. Example 4 Graph the half‐open interval (see Figure 8). { x: –1 < x ≤ 2} Figure 8. A graph showing half‐open interval { x: –1 < x ≤ 2}.

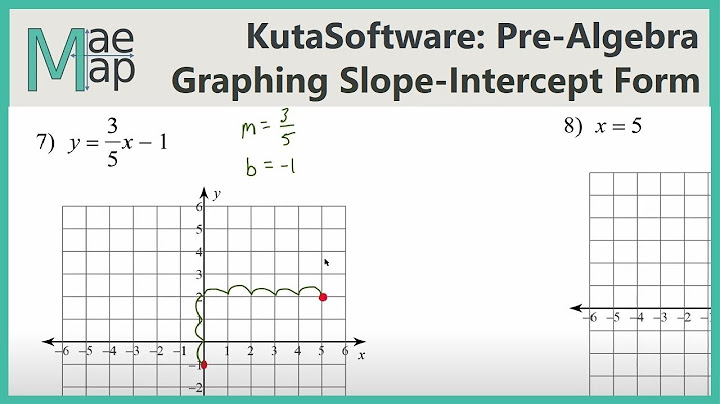

Video transcriptI'm starting to take a little bit more care of my health, and I start counting my actual calories. And let's say C is equal to the number of calories I eat in a given day. And I want to lose some weight. So, in particular, I want to eat less than 1,500 calories in a day. So how can I express that as an inequality? Well, I want the number of calories in a day to be less than-- and remember, the less than symbol, I make it point to the smaller thing. So I want the calories to be less than 1,500. So this is one way of expressing it. I say, look, the number of calories that I consume in a day need to be less than 1,500. Now, one thing to keep in mind when I write that is obviously if I eat no calories in a day, or if I eat 100 calories, or if I eat 1,400 calories, or if I eat 1,499 calories for C, those are all legitimate. Those are all less than 1,500. But what about 1,500 calories? Is it true that 1,500 is less than 1,500? No. 1,500 is equal to 1,500. So this is not a true statement. But what if I want to eat up to and including 1,500 calories? I want to make sure that I get every calorie in there. How can I express that? How can express that I can eat less than or equal to 1,500 calories, so I can eat up to and including 1,500 calories? Right now, this is only up to but not including 1,500. How could I express that? Well, the way I would do that is to throw this little line under the less than sign. Now, this is not just less than. This is less than or equal to. So this symbol right over here, this is saying that C is less than or equal to 1,500 calories. So now 1,500 would be a completely legitimate C, a completely legitimate number of calories to have in a day. And if we wanted to visualize this on a number line, the way we would think about it, let's say that this right over here is our number line. I'm not going to count all the way from 0 to 1,500, but let's imagine that this right over here is 0. Let's say this over here is 1,500. How would we display less than or equal to 1,500 a number line? Well, we would say, look, we could be 1,500, so we'll put a little solid circle right over there. And then we can be less than it, so then we would color in everything less than 1,500, and say, look, anything less than or equal to 1,500 is legitimate. And you might say, hey, but what about the situation where it wasn't less than or equal? What about the situation if it was just less than? So let me draw that, too. So going back to where we started, if I were to say C is less than 1,500, the way we would depict that on a number line is-- let's say this is 0, this is 1,500, we want to make it very clear that we're not including the value 1,500. So we would put an open circle around it. Notice, if we're including 1,500, we fill in the circle. If we're not including 1,500, so we're only less than, we were very explicit that we don't color in the circle. But then we show that, look, we can do everything below that. Now, you're probably saying, OK, Sal, you did less than, you did less than or equal, what if you wanted to do it the other way around? What if you wanted to do greater than and greater than or equal? Well, let's think about that for a second. Let's say that I'm also trying to increase the amount of water I intake. And so let's define some variable. Let's say W is equal to the number of ounces of water I consume per day. And I've read that I should have at least-- let me throw out a number-- 64 ounces of water per day. There's one way I could think about, where I always want to drink more than 64 ounces, so that would be W is greater than 64. W here is the thing that I want to be bigger, so the opening is to the W. W is greater than 64 ounces. How would I depict that? Well, let me do my number line right over here. Let's say that this is 0. This is 64. If I wanted to make strictly greater than, so in this situation it's not cool if I just drink exactly 64. That 64 is not greater than 64. I have to drink 64.01 ounces or 0.00001 ounces. It has to be something that is greater than 64. So I'm not going to include 64, but anything greater than that is completely cool. Now, what if I want to loosen things a little bit? It's OK if I drink exactly 64 ounces or more. Well, then I could write W is greater than or equal to 64. And the way that I would be depict that on the number line-- and obviously, I'm not showing all the numbers in between-- let's say this is 0, and then we go all the way up to 64. Well, now it's OK if I drink exactly 64 ounces, so I'm going to fill in the circle now. Here I opened it because 64 was not a cool number. Now, 64 is completely OK. I can drink exactly 64 ounces of water in the day or more, and then I just go up the number line just like that. What does x =Pre-Algebra Examples

Since x=−3 is a vertical line, there is no y-intercept and the slope is undefined.

|

Advertising

LATEST NEWS

Advertising

Populer

Advertising

About

Copyright © 2024 pauex Inc.